The government has two main ways it tries to influence the economy – through Fiscal Policy and Monetary Policy. Fiscal policy is the more direct approach, where the government levies taxes and subsidies to try to balance its budget while encouraging growth, while monetary policy is less direct – tweaking interest rates and modifying the money supply.

What is the Money Supply?

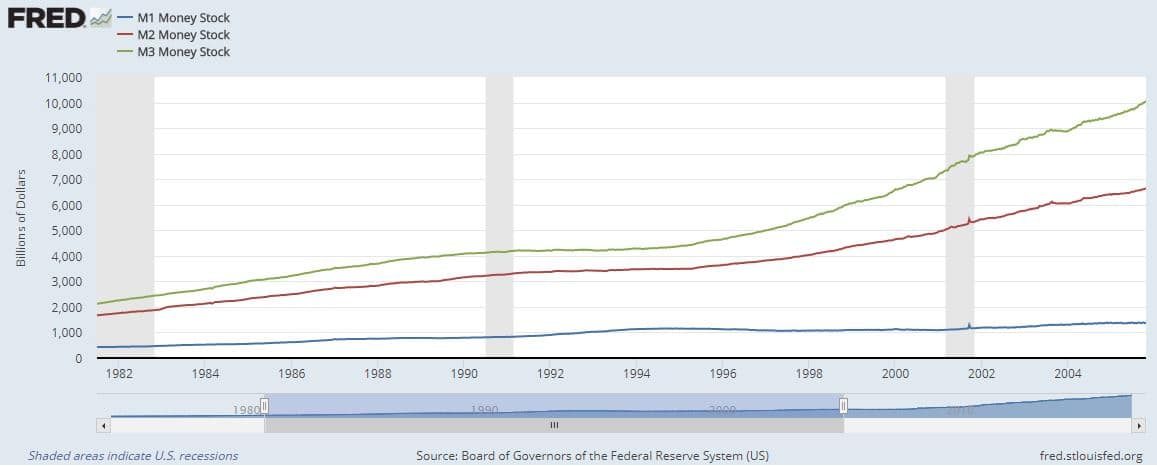

The money supply is the total amount of money in circulation at any given time. This number will be quite different depending on what type of money you look at. Economists generally group the “money supply” into four categories based on liquidity. The more liquid the type of money (meaning how easily it can be spent), the more restrictive its money supply category.

M0 – Cash

M1 – Cash + Checking Accounts

The next level up is M1 – or “liquid money”. This is all money which can easily be spent immediately, so it includes both cash and checking accounts. M1 is much bigger than M0, since most people usually hold a lot more money in their checking accounts than they do as cash.

M2: Cash + Checking + Saving

M2 is even bigger – it includes everything in M1, plus anything deposited into savings accounts and some Certificates of Deposit. This is in a separate category because there is another level needed before this money can be spent. Usually you would need to transfer money from your savings account into your checking account before you can spend it, making it slightly less liquid. M2 is sometimes called “Near-Money” because of the need to make a transfer before you can spend it. This is the most commonly-used measure of the money supply as an indicator of economic growth.

M2 is very commonly used as a stand-in for “Money Supply”. Because it includes most types of deposits, it includes the “Money Multipliers” from fractional reserve banking (see our article on How Money is Created for details).

M3: Cash + Checking + Saving + Money Markets

M3 is even bigger than M2 – it also includes high-interest savings accounts that put restrictions on withdrawals. These are called “Money Market” accounts (or some bigger Certificates of Deposit also qualify). With these accounts, the depositor gets a higher interest rate than a typical savings account, but they need to maintain a very high minimum balance, and are limited on how many times they can withdraw.

Because of these restrictions, money market accounts are “less liquid” than normal savings accounts.

Monetary Policy – The Big Picture

Monetary policy is set by the Federal Reserve Bank, not by Congress and the President. This is important, because it means that monetary policy is usually more removed from the normal “politics” of Washington. The Federal Reserve has two main objectives for monetary policy: encouraging economic growth, while controlling inflation.

Inflation and Growth

Taking out loans causes the money supply to grow, while paying it back will cause the money supply to shrink. This means over the entire life of the loan (from initially borrowing it to fully paying it back), the money supply does not change. However, businesses will spend the loan before paying it back, putting that money into circulation.

If the economy is growing, it means more people are taking out loans today than they were yesterday. This means that the money supply grows before the rest of the economy – which causes some inflation.

Inflation caused by growth – example

- Step 1: Business takes out a loan (increasing the money supply)

- Step 2: Business uses the loan to hire a new employee, and pays the new employee their first paycheck (putting the money into circulation)

- Step 3: The business provides a service to one of its clients, and gets paid for it (generating a profit)

- Step 4: The business pays back its loan

In this example, the business pays its employee, and the employee spends their paycheck before the business gets paid by its client, and pays back its loan. This means that while businesses take out loans to drive growth, that money enters the economy before new value is added (meaning the growth the business causes). In the time between when the employee is paid and the business provides its service to the client, money was added to the economy, but no growth was added. More money but no growth means a small amount of inflation.

This same cycle is repeated millions of times every week, with people and businesses taking out and paying back loans. Since there will always be a time delay, the money supply needs to grow before the rest of the economy: the source of “Inflation by Growth”.

Runaway Inflation

This means prices continue to rise without any extra value added to the economy. In real terms, the effect is that individual’s savings loses its value, and paychecks are worth less.

The Federal Reserve uses monetary policy to maintain the balance between inflation and growth: encouraging businesses to borrow and grow, but deterring runaway inflation.

Tools of Monetary Policy

The Federal Reserve has three tools at its disposal when determining money supply: Interest Rates, Reserve Requirements, and Bond Buying.

Manipulating Interest Rates

This is the biggest tool in the box. The Federal Reserve directly sets what is called the “Federal Funds Rate”, which is the interest rates at which banks lend money to each other. This is the baseline “risk free” interest rate for banks, so if the Federal Funds rate goes up, all other interest rates go up, discouraging borrowing. If the Federal Funds rate goes down, all other interest rates go down, which encourages borrowing.

Every month, the Federal Reserve monitors all economic data across the United States, and meets to discuss inflation and growth levels. If it looks like inflation is pushing too high, they will increase the Federal Funds rate. This will decrease the total number of new loans that people and businesses take out, pushing down the inflation rate.

If it looks like the economy is struggling to grow, they do the opposite – lowering the federal funds rate to encourage borrowing and growth. The Federal Reserve changes the interest rates frequently to match the economy – there will be an announcement of the next month’s policy (go up, go down, or stay the same) every month.

Reserve Requirements

Another tool they can turn to is changing the reserve requirements for banks. At the end of each day, banks need to keep a certain percentage of deposits “in the vault”, or not loaned out. This is called the “Reserve Requirement”, and it puts a hard limit on how much money banks can loan out at any given time.

If inflation is high but growth is low, the Federal Reserve can lower the reserve requirement. This will let banks make more loans to fuel growth, but still keep the interest rates high to try to fight inflation. This is a one-way tool – if the Federal Reserve lowers the Reserve Requirement, when the economy does start growing again they will need to raise it back up (or risk not being able to use this tool in the next crisis). Reserve Requirements do not change very often – usually less than once per decade.

Bond Buying

Bond Buying, or Quantitative Easing, is the most extreme form of monetary policy. This is a new tool that was developed in response to the 2007 economic crisis, when inflation and growth were both low, but interest rates could not be lowered.

When investors and businesses think that the economy is shrinking, they tend to pull their money out of markets and into “risk-free” assets like bonds, where they have a guaranteed return. Buying bonds in large numbers decreases the money supply, since it pulls the money out of banks and circulation. Less money available means less loans, and less growth overall – the money supply needs to be growing for the economy to grow.

For this tool, the Federal Reserve buys huge quantities of bonds from the Treasury, then immediately sells then on the open market. This floods the Bonds market, lowering the prices (and returns) for bonds. Business and investors then see bonds as a “less profitable” investment, pulling their money back into other businesses and investments, increasing the money supply, and opening the door to growth.

Volume Weighted Average

Volume Weighted Average